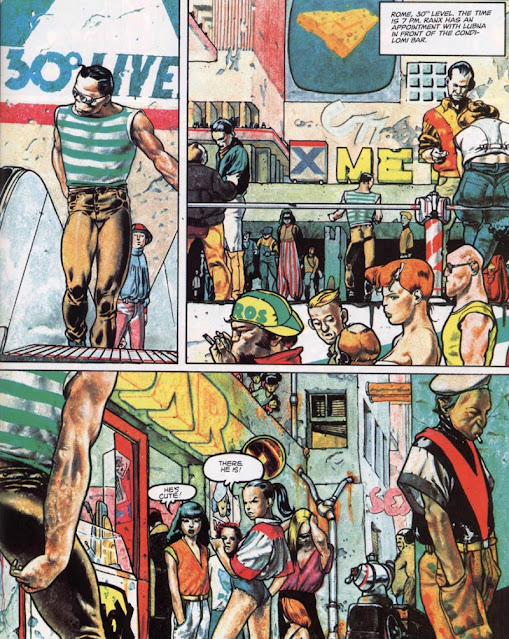

There are no human beings in Stefano Tamburini and Tanino Liberatore’s mannerist cyberpunk fantasy world, only monsters. Cleaved, free-floating impulses disguised as people roam the dystopian cityscapes: the ferocious cyborg bully boy Ranxerox is only the most explicitly inhuman, but really, none of Tamburini and Liberatore’s characters are anything more than behaviourist “flesh machines” animated by simple, imperative desires. Insatiable appetites possess athletic frames with mindless animal ardor; feral ire and disgust abide in the hard little bodies of vamp assassins and heroin-shooting nymphet prostitutes; brutal lust and contempt can live indifferently within the fearful symmetry of fashionable patrician elegance or in the dumpy ugliness and ordinary deformity of the everyman. Everywhere, vulgar mugs leer and snarl and bite and lick and suck; powerful limbs kick and punch and squeeze and stab and crush. Since the characters have no depth, we accept that their bodies are merely the splendid impersonal paraphernalia necessary for fucking, for narcotic gratification, for assault and mayhem. Witness this skin fold, that roll of flesh; notice the ductile integument pulled taut over shifting sculptural configurations of muscle, bone, fat, connective tissue... The glorious integrated complexity of anatomical patterns swell like ripe pornographic fruit in each comic panel — just asking for it. Each human form is a miraculous balance of carnal vitality — but in this future hell of lust and fury, it exists only to be broken savagely, to be pulled apart with a child’s inquisitive cruelty. Veins bulge, blood spurts, sensitively textured flesh swells or sags or splits apart; cruel predators, narcissistic perverts, psychopathic fiends, casual murderers — sexy beasts all — mingle in knots of camp intensity… Each character is an object for the other to use and abuse in search of satisfaction.

In his little book about Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, Gilles Deleuze makes the argument that, far from being symmetrical, sadism and masochism are in fact incommensurable. In his view, masochism is about the tight containment and security that an explicit contract provides: pain will be meted out, but only within finely modulated parameters, agreed upon between contracting parties. There is no real loss of control, only the delicious temporary delegation of it. Sadism, on the other hand, is about transgressing any constraining norm to affirm an undomesticated, domineering self and destroy any competing claim to selfhood. So although gimp masks, slick bodysuits, and restraints appear from time to time in Liberatore’s art, it seems to me they are merely convenient visual markers for “deviance.” He likes his characters to be “freaks” and “perverts” but he’s not actually that interested in the dynamics of masochism itself. Tame masochists do however make good fodder for his psycho sadists — the real focus of his imaginative efforts — because attacking the former enhances the shock value of his flamboyant psychos’ real violations: masochists play by the rules, but the point is that his perfunctory killers do not.

None

of this is to be taken seriously, of course. It’s all a bit of a joke. Punk

bravado: ironically flaunting deliberate, aggressive ugliness as an aesthetic

posture to protest the outrageous fact that there will be in fact “no future.”

Ironic also the heady incongruity of rendering the most bestial impulses with

such artful sensitivity — but then art is meant to be about sublimating our

baser instincts, isn’t it? Surely Michelangelo himself — obviously Liberatore’s

spirit animal — would have felt less compelled endlessly to represent such

vital, heaving, superlative bodies had he instead simply followed his baser

instincts and, once in a while, let himself get sucked off in the bogs?

In Michelangelo's art, the human form is the one expressive motif fit to carry, to embody, to express the soul's mighty struggle to find salvation. Liberatore's farcical cyberpunk romp has, of course, no such momentousness of purpose: we are merely offered the cruel/comedic/pornographic spectacle of vigorous bodies gleefully and mercilessly pressed against the unyielding dystopian environment that contains their helplessness and their ire — the cold hardness of metal, the dumb weight of concrete, the rude tumult of other bodies... And this science fiction future of Liberatore’s isn’t the real future; it’s merely an extravagant, stylised projection of the “present” (the late 1970s and early 1980s) because the real future, like our own death from our subjective perspective, is probably unimaginable and must remain forever at a prophylactic distance. Although there’s plenty of death and destruction in these stories, it’s never real death: on the contrary, I suspect these pictures to be controlled exorcisms. They channel the lingering existential echo of fearsome childhood rages of the kind that know no limit and desire the total annihilation of the other — that outrageous obstacle to fulfilment. In their own way, these evocations of primal brutality are life-affirming rituals — plugged into an authentic, visceral early experience, despite the artist's posture of arch, ironic distance. It strikes me that what is powerful about them is the genuine sense they give of the fragility of our embodiment (threatened by violence and madness, withered by dope addiction and old age, enslaved by sex and relentless desire…). In a soulless world, we can’t help suspecting that, like the punk Frankenstein monster RanXerox, we are not more than the sum of our parts.

No comments:

Post a Comment